|

Dr Nebogipfel,

I presume?

A wonderful, thorough, 'must-have'

annotated edition of The Time Machine

"Apart from its outstanding literary repute, The Time Machine is

remarkable for its 'complex bibliographical history,

which must be unparalleled among works of modern fiction' (Begonzi 1960:42; see also Lake

1980). Begun in 1888 as an amateur effort, it went through six drafts, three of them

published (see appendices I-III) before it appeared in two different versions in New York

and London (1895b and 1895c), and even then Wells did not stop tinkering with it until one

last refinement done for The Scientific Romances of H.G. Wells (1933a).

From the Introduction to Leon Stover's The

Time Machine : An Invention : A Critical Text of the 1895

London First Edition, With an Introduction and Appendices

(Annotated H.G. Wells, 1)

Considering the fact that you can buy a paperback for a few dollars... or

even read the complete text right here on

the site... is it worth shelling out $49.95 for this edition? Well,

if you already know what an 'amateur cadger' is, or what it means when

they 'plow you for the little-go,' then I guess you could skip it. But

if these and other Wells references, phrases, and allusions are lost

on you, getting Stover's book is a treat.

It would be worth $149.95. Or even $249.95. At $49.95, it's a downright steal. Buy it!

If you travel to the future... make this one of the three books you take. (By the way,

clicking on any of the book titles on this page will take you to its Amazon.com listing)

Stover's omnibus contains many of the variations, focusing on the text of the

1895 London First Edition. Annotations explain all the textual references, which

adds immeasurably to the reader's enjoyment. The notes are easily accessed - with footnote

numbers appearing in the text and the corresponding annotation appearing at the bottom of

the very same page. (Indeed, the annotations probably contain as many words as the text

itself!) While Wells' prose is every bit as entrancing and engrossing as it was over a

hundred years ago, certain topical references and obscure allusions which might otherwise

be lost are made clear through Stover's incisive (and exhaustive) annotation. This edition

also includes alternate versions of The Time Machine by Wells, notably "The

Chronic Argonauts," the earliest version of the story: dark, haunting, and radically

different from the versions to come. In "The Chronic Argonauts," which first

appeared in The Science Schools Journal in 1888, you lean that the unnamed Time

Traveler of the classic text was originally named Dr. Moses Nebogipfel.

The book also contains Wells' second revision, "The Time Traveler's

Story," which appeared in The National Observer in 1894.

Also included are excerpts from the Heinemann edition of The Time Machine, which was

taken from a serialized version published during the first half of 1895. Was Wells correct

in excising the "ghastly rabbits and centipedes" as the descendants of the Eloi

and Morlocks? You can read it for yourself and decide.

I am a Chronic Argonaut, an explorer of epochs, a man for all

time, a Morlock fighter...

Another Annotated edition with interesting bonuses

Childhood fears also left their mark on The Time Machine. At the age of seven,

Wells, poring over a copy of John George Wood's The Boy's Own Book of Natural History,

"...conceived a profound fear of the gorilla, of which there was a fearsome picture.

[I imagined that it came] out of the dark and followed me noiselessly about the

house. The half landing was a favorite lurking place for this terror. I passed it

whistling, but wary and then ran for my life up the next flight."

From the Introduction to Harry M. Geduld's The

Definitive Time Machine : A Critical Edition of H.G. Wells's Scientific

Romance

This text for this definitive text comes from the 1924 Atlantic edition of Wells's

"The Time Machine." The annotations here are far less conveniently located than

in the Stover edition. They're grouped together at the conclusion of the text, and there

are no footnote numbers - just chapter and page references, so the reader has to do a bit

of searching to find the text being commented upon.

Includes four pages of material "which does not appear in any previously published

edition of The Time Machine" - an alternate ending in which the Time Traveler (named

"Bayliss" in these fragments!) "...loses his Time Machine after being

ejected from it." A longer fragment describes the return of the Time Traveler, his

sojourn in 2,000,000 B.C. and his arrival on New Year's Day of 1645, where the locals

shoot at him... before he returns to his own time. The short fragments come from the

H. G.

Wells Collection of the University of Illinois Library at Urbana-Champaign.

Also appearing in this volume are "How To Construct A Time Machine," by

Alfred Jarry... and an intriguing excerpt from Terry Ramsaye's history of the early

cinema, "A Million and One Nights," concerning Robert W. Paul.

Paul patented a 'virtual reality' theme-park-style ride -- in 1895. Based on the idea

of presenting time travel using brand-new motion picture technology, the invention,

according to Paul, "...consists of a platform, or platforms, each of which contains a

suitable number of spectators and which may be enclosed at the sides after the spectators

have taken their places... In order to create the impression of traveling, each platform

may be suspended from cranks in shafts above the platform... placed so as to impart to the

platform a gentle rocking motion, and may also be employed to cause the platform to travel

bodily forward through a short space. The films or slides are prepared with the aid of the

kinetograph or special camera, from made up characters performing on a stage..."

Not bad, considering that the narrative movie was still nearly two decades away, and

the platform-based thrill-park ride wouldn't show up for nearly another hundred

years!

Suddenly, out of the

blue, The 1895 Holt Time Machine materialized in 1969...

Children's edition (mistakenly?) uses text of disavowed New York first printing

| The Time Machine and The Invisible Man. Annotated;

Complete and unabridged. Illustrated by Dick Cole, Cover by Don Irwin. Classic Press

Incorporated/ Children's Press, 1969. LOC 70-79993 |

The first time I saw this large, school-bookish-looking edition of "The Time

Machine," I was puzzled.

The opening paragraph was completely different from the book I knew. My initial thought

was that I was reading an adaptation especially created for school children. But why,

then, did the title page state "complete and unabridged?" Further, if this was

an adaptation, why offer definitions of obscure words (sometimes supplemented by pictures)

in the extra-wide margins? Why not simply re-phrase?

The answer: this edition reprints an early version of the story -- one that Wells later

disavowed. This collectable curiosity makes for fascinating reading, reprinting as it does

the text of the U.S. Holt edition.

Geduld on this version of the story:

The British edition of The Time Machine published by Heinemann in 1895 is

often referred to as the first edition.

In fact, it was not issued until 29 May 1895, whereas the American edition,

published by Henry Holt and Co., was published on 7 May or earlier. The

Holt version differs in a number of important respects and in numerous

stylistic details from both the New Review Text [a serialized version

which appeared in the New Review from January through May of 1895].

For example, Chapter 1 of the Holt text looks like a curious blend of

passages from both the National Observer and the New Review

versions -- although [Wells Scholar] Philmus believes that the Holt text

probably antedates the New Review Version -- and the New Review

and Heinemann versions conclude with the memorable, poetic epilogue, while

the Holt version ends rather blandly with a terse account of what had

become of the Time Traveler's guests during the period of his disappearance.

On the basis of textual collation, [Wells Scholar] Bergonzi concludes:

'There is a very strong probability that' the Holt version is 'an early

and unrevised version' of the New Review and Heinemann texts. 'Wells

may have virtually disowned the New York edition since it represented

an unrevised text, and this may account for his subsequent silence about

it.'"

I strongly suspect that the publishers of the 1969 edition were either unaware of their use

of a variant text, or were perhaps in some way the business successors to Holt.

(Imagine the problems that may have been created when a student scholar, using this

volume, makes references to passages and events which do not appear in the text belonging

to that student's teacher, who's using a paperback edition for convenience!)

I searched and searched for a copy of this, before I even realized what it was. I

had only seen a copy in the Children's Section of a local library... and was intrigued by

the curious content, marginal notations, and odd pen and ink illustrations. I

finally found and purchased a fine copy on eBay for about $6... quite a bargain, I think,

now that I appreciate what I got.

Worth seeking out, but rare -- use "Cole" as a keyword in your searches (the

illustrator) to locate this edition.

| The FIRST version of The Time Machine was titled "The Chronic Argonauts" and

appeared in Science Schools Journal, the students' magazine of the Royal College of

Science, serialized over April, May, and June of 1888. |

| The SECOND and THIRD versions were produced by Wells between 1889-1892. These versions

are lost. |

| The FOURTH Version is the National Observer Version (substantially shorter than the

Atlantic version, the text most commonly reprinted today) and appeared in that publication

between March through June 1894, though it was never finished. In this version, The Time

Traveler visits 12,203 rather than 802,701. |

| The FIFTH version is the New Review text, "closer," according to Geduld,

"to the final book version than it is to the National Observer serialization"

Published in New Review between January through May of 1895. |

| The SIXTH version is the Holt edition, the one reprinted in the volume currently under

discussion. |

| The SEVENTH version is the Heinemann edition of 1895, the first British publication of

The Time Machine in book form. |

| The EIGHTH version first appeared as the first volume in the Atlantic Edition of The

Works of H.G. Wells, and is today considered the standard text. According to Geduld, the

"divergencies from the Heinemann edition are all quite minor. Geduld's Definitive

Time Machine reprints the Atlantic text; Stover reprints the 1895 Heinemann edition...

|

Opening Paragraph, HOLT EDITION: The

man who made the Time Machine - the man I shall call The Time Traveler

- was well known in scientific circles a few years since, and the fact

of his disappearance is also well known. He was a mathematician of peculiar

subtlety, and one of our most conspicuous investigators in Molecular physics.

He did not confine himself to abstract science. Several ingenious, and

one or two profitable, patents were his: very profitable they were, these

last, as his handsome house at Richmond testified. To those who were his

intimates, however, his scientific investigations were nothing to his

gift of Speech. In the after dinner hours he was ever a vivid and variegated

talker, and at times his fantastic, often paradoxical, conceptions came

so thick and close as to form one continuous discourse. At these times

he was as unlike the popular conception of a scientific investigator as

a man could be. His cheeks would flush, his eyes grow bright; and the

stranger the ideas that sprang and crowded in his brain, the happier and

more animated would be his exposition.

Opening Paragraph, ATLANTIC EDITION: The

Time Traveler (for so it will be convenient to speak of him) was expounding

a recondite matter to us. His grey eyes shone and twinkled, and his usually

pale face was flushed and animated. The fire burned brightly, and the

soft radiance of the incandescent lights in the lilies of silver caught

the bubbles that flashed and passed in our glasses. Our chairs, being

his patents, embraced and caressed us rather than submitted to be sat

upon, and there was that luxurious after-dinner atmosphere when thought

roams gracefully free of the trammels of precision. And he put it to us

in this way--marking the points with a lean forefinger--as we sat and

lazily admired his earnestness over this new paradox (as we thought it:)

and his fecundity.

Closing Paragraph, HOLT EDITION: But I am

beginning to fear now that I must wait a lifetime for that. The Time Traveler

vanished three years ago. Up to the present he has not returned, and when

he does return he will find his home in the hands of strangers and his

little gathering of auditors broken up forever. Filby has exchanged poetry

for playwriting, and is a rich man -- as literary men go -- and extremely

unpopular. The Medical man is dead, the Journalist is in India, and the

Psychologist has succumbed to paralysis. Some of the other men I used

to meet there have dropped as completely out of existence as if they,

too, had traveled off upon some similar anachronisms. And so, ending in

a kind of dead wall, the story of the Time Machine must remain for the

present at least.

Closing Paragraph, ATLANTIC EDITION: One

cannot choose but wonder. Will he ever return? It may be that he swept

back into the past, and fell among the blood-drinking, hairy savages of

the Age of Unpolished Stone; into the abysses of the Cretaceous Sea; or

among the grotesque saurians, the huge reptilian brutes of the Jurassic

times. He may even now--if I may use the phrase--be wandering on some

plesiosaurus-haunted Oolitic coral reef, or beside the lonely saline lakes

of the Triassic Age. Or did he go forward, into one of the nearer ages,

in which men are still men, but with the riddles of our own time answered

and its wearisome problems solved? Into the manhood of the race: for I,

for my own part cannot think that these latter days of weak experiment,

fragmentary theory, and mutual discord are indeed man's culminating time!

I say, for my own part. He, I know--for the question had been discussed

among us long before the Time Machine was made--thought but cheerlessly

of the Advancement of Mankind, and saw in the growing pile of civilization

only a foolish heaping that must inevitably fall back upon and destroy

its makers in the end. If that is so, it remains for us to live as though

it were not so. But to me the future is still black and blank--is a vast

ignorance, lit at a few casual places by the memory of his story. And

I have by me, for my comfort, two strange white flowers --shrivelled now,

and brown and flat and brittle--to witness that even when mind and strength

had gone, gratitude and a mutual tenderness still lived on in the heart

of man.

Page under construction - reviews of these editions to come. This is the

Random House "Art Deco" version, with Eloi that look like Joan

Crawford. It's slipcased and surprisingly easy to find.

Page under construction - reviews of these editions to come. This is the

Random House "Art Deco" version, with Eloi that look like Joan

Crawford. It's slipcased and surprisingly easy to find.

This is a Dover Thrift Edition... under a buck.

This is a Dover Thrift Edition... under a buck.

This

is a really nicely illustrated children's abridgement, currently available. This

is a really nicely illustrated children's abridgement, currently available.

The Movie Tie-in paperback.

The Movie Tie-in paperback.

Two Books...

Which would you choose?

This in-print Dover

Edition sells for 80 cents, brand new, at Amazon.com.

This in-print Dover

Edition sells for 80 cents, brand new, at Amazon.com.

An out-of-print first edition (similar to this one) is on the market for

$25,000.00.

An out-of-print first edition (similar to this one) is on the market for

$25,000.00.

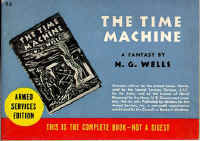

ARMED SERVICES EDITIONS were cheaply

produced and distributed free in the expectation that they would not only

be read, but read up, as well. As it happened, some GI's brought copies

home when they came back from the war; and even today, odd ASE volumes

are easily and cheaply acquired in second-hand bookshops (the going rate

for run-of-the-mill copies is about $2).

Typical

British first editions of The Time Machine sell from $750 to $2500. If

you'd prefer to spend more money than that for a copy that is distinguished

primarily by the misspelling of "H.G. Wells," contact James

Pepper Rare Books, Inc., 2026 Cliff Drive, Suite 224, Santa Barbara, CA

93109 USA, which offers this incredibly rare presentation copy for $32,000.00.

WELLS, H.G: The Time Machine. An

Invention ; 4181J London William Heinemann 1895 First English

Edition. This is the only known copy in cloth with the author�s name misspelled

�H.S. Wells� on the front cover. The Time Machine was issued a few weeks

earlier in America by Henry Holt and curiously the earliest Holt copies

were misspelled �H.S. Wells� on the title page. As this is Wells� first

book and he was then a virtual unknown, it is easy to see how such a mistake

occurred. Well�s name is spelled correctly on the title page of all known

English copies but amazingly this single copy exists stamped with the

error on the binding. The English first edition has always been a complicated

affair which noted science fiction bibliographer L.W. Currey has attempted

to reveal and he has recorded six different types of copies in wrappers

and cloth. This copy conforms to none of Currey�s copies. This copy is

bound in a light tan cloth as opposed to the usual gray cloth; measures

18.2 centimeters vertically; the top edges rough trimmed and the fore-edges

untrimmed and does not have a publisher�s catalogue. The front cover is

stamped with the winged Egyptian lion with the Pharoah�s face as present

in the regular English copies though the stamping is a warmer shade of

purple than the usual dark purple stamping. The �T� in the first word

of the title in the spine is a different type face from the rest and the

title stamping on the front cover is two tenths of a centimeter small

than normal copies. The possibility exists that this is a single trial

copy. Spine darkened, and some very minor stains to rear cover, otherwise

very good to fine. Obviously, this is the earliest existing copy of the

first English edition in cloth. Wells� finest work and along with Frankenstein,

the most influential piece of 19th century science fiction. Enclosed in

a custom slipcase.

Don

Brockway, March 1, 2000 (updated October 12, 2004)

[ Early

Editions ] [ The

Book ] [ The

Time Machine Home Page ]

|